New route on Santa Cruz Chico, 5,800m, by GTAIB

Directíssima Mallorquina” (520m, MD+)

After two weeks of acclimatization in the Cordillera Blanca, during which we climbed mountains such as Vallunaraju, Yanapaccha, and Shacsha Sur, we decided to go a little further in search of a new line. After a day wandering among maps and books from the comfort and warmth of our house in Huaraz, an imposing, isolated, and seemingly untouched wall, of which we only had two rather archaic images, had taken root in our minds. Overnight, this wall went from being a simple daydream to becoming the focus of all our energy. It was the west face of Santa Cruz Chico, a remote 5,800m peak with only one recorded ascent back in 1958, and now, 67 years later, it was calling to us strongly to be climbed for the second time.

On July 7, at 06:30, the five members of the group: Cati Lladó, Tomeu Rubí, Lluís Dietrich, Guillem Anguera, and Miquel Àngel Lorente, set off from Hualcayan, together with a muleteer and his two donkeys, who carried what we needed to spend the next four days in the mountains. After five hours of climbing uphill we crossed a pass and saw our objective for the first time. It was still far away, but it seemed to be in good condition for an attempt.

Several hours later, we reached a plateau at about 4,500m, where we set up base camp and said goodbye to the muleteer and his animals. That evening, while having dinner, we enjoyed the last light illuminating Santa Cruz Chico (center) and its two bigger brothers: Santa Cruz Norte (5,829m) to the left, and Santa Cruz Grande (6,259m) to the right.

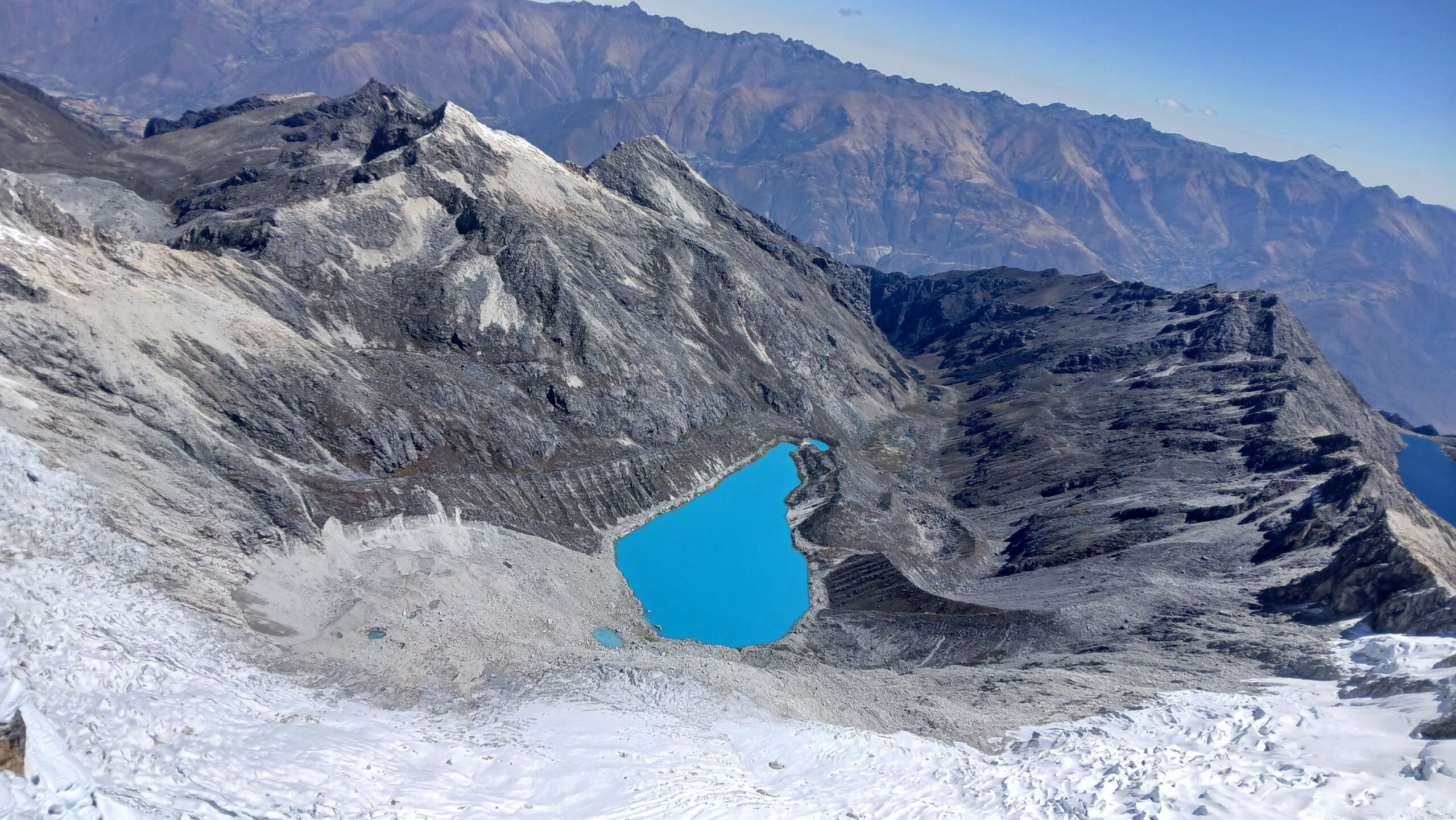

The next morning, we packed our backpacks with the intention of finding a spot closer to the wall to establish an advanced camp. For reasons of safety, comfort, and access to water, we found the right place on the shores of Laguna Yuraccocha. After setting up the tents, we spent the rest of the morning exploring the approach to the glacier, and from its edge we searched with our eyes for weaknesses in the wall through which we could attempt the summit the following day. After some debating and weighing options, we concluded that the best line would be the most direct, climbing as vertically as possible, always under the summit’s plumb line. That afternoon, as we packed our gear, the silence was deafening, and the air heavy. A strange tension could be felt, different from what we had experienced many times before. The uncertainty of facing a virgin wall is not comparable to repeating an established route. At 18:00, with our packs ready and a cocktail of emotions keeping our minds restless, we crawled into our tents to try to get some sleep.

That same night, at 00:00, the piercing sound of the alarm pulled us from the warmth of our down sleeping bags. We ate breakfast and dressed inside the tents, and before heading out we slipped into our warm Bestard Top Extreme Lite boots, which had spent the night with us inside the bags. At 01:00, we set off decisively towards the glacier, following the cairns we had left the previous day. Upon reaching the glacier, we roped up and began to search for the best path to the base of the wall. That night, the Moon shone brightly and helped us navigate through the crevasses and seracs of the glacier, which stood harsh and unforgiving in the immensity of the night.

At 03:30 we arrived at the start of the route. The wall greeted us with excellent climbing conditions: pitches of firm snow and solid ice that allowed us to progress at a lively pace, bearing in mind that what would be considered a decent pace at 5,000m would seem painfully slow at lower altitude, where breathing freely is taken for granted and not a luxury for the well-trained. Pitch after pitch, hour after hour, the darkness slowly gave way to light. We kept climbing.

Daylight shone brightly, but on a west face in the southern hemisphere, we had to content ourselves with watching the sun illuminate the lake and valley behind us. Above, an endless wall.

Belay after belay, we could not yet see the summit, but it already felt near. At noon, the sun began to peek above the mountain, hitting our faces and keeping us awake.

Pitch 11. We did not yet know it, but this would be the final one. Suddenly, the snow quality deteriorated drastically, and ice was nowhere to be seen. Progress slowed pathetically, and we had to dig a trench in the “y-axis” just to be able to move upward. Sometimes we had to chimney against the trench walls, careful not to collapse them, and other times crawl like worms up short snow ramps that felt endless.

Finally, as exhausted as we were happy, at 16:30 we all stood on the summit of Santa Cruz Chico. We enjoyed the view and the peak for just three minutes, and then, as if struck by urgency, began the descent.

We decided to rappel down the same route, as it seemed the safest option and we already knew what awaited us. The ridge leading to the col between Santa Cruz Chico and Santa Cruz Norte looked impassable.

The monotony of rappelling more than 500m of wall and eventually at night, seeing only what was lit by our headlamps, turned into an extremely tedious and mentally exhausting task.

The temperature began to drop; noses and cheeks reddened in the air, and our hands felt cold as they handled the rope. However, our feet, which had remained just centimeters from snow and ice all day, were still as warm as when we had left our sleeping bags that morning, something that not only allowed us to function in freezing conditions, but also to enjoy the climb more. After five hours of rappelling we reached the base of the wall. It was 21:00, and we still had to retrace our steps back to the comfort of our sleeping bags, waiting impatiently to embrace us for the rest of the night. The hike back was as soporific as the rappels, and the few cognitive resources we had left were devoted to not tripping and placing our feet carefully on the rocks of the moraine that led back to the advanced camp.

At 23:30, the glow of our headlamps finally illuminated the tents. We had returned to the very spot we had left 22 and a half hours earlier. And although “only” a day had passed and nothing around us seemed to have changed, we were not the same as when we had set off the night before. These had been hours of focus and collective effort toward a shared goal, during which we had learned, suffered, and enjoyed, binding us more closely to the mountain and to our rope partners.

In this climb, technical equipment played a key role. The Bestard Top Extreme Lite boots were our allies at all times. They are boots designed for high-altitude mountaineering, light yet robust, with a double liner that ensured insulation during a day of more than 20 hours. Their design allowed us to move confidently both on the glacier and on the ice pitches, without compromising precision on footholds. That combination of comfort and protection was decisive in keeping both motivation and safety until the very end.

On July 9, 2025, the GTAIB opened a new line on Santa Cruz Chico, a 520-meter route graded MD+, which we proudly baptized as the Directíssima Mallorquina. A route that will remain in the group’s history, and also further proof that with the right gear and the necessary determination, even the most demanding mountains can become the setting of our best memories.